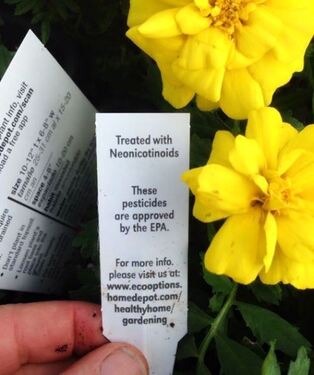

Each container’s small plastic ID label serves as a helpful guide to pick and choose the perfect plants, but there’s another that says the plant has been treated with neonicotinoids. What does that mean, and should you be concerned?

Yes, you should be very concerned. Do not purchase them.

Neonicotinoids, or neonics, are a systemic insecticide, meaning the poisons are dispersed throughout the whole plant to prevent pests from nibbling on your leaves, buds, and blooms. That’s what the salesperson will tell you, but that’s not the whole truth. These toxic chemicals are non-selective and do not differentiate between pests and beneficial insects. It is an equal opportunity killer. If you plant these flowers, the bees and butterflies you dreamed of visiting your garden will not receive the friendly welcome you intended.

Neonicotinoids and other systemic insecticides pose an additional risk of delayed exposure to the poison since they can persist in plants and the environment for months to years after application. Regrettably, the use of neonics by homeowners and commercial food producers is widespread across the US. The terrible thing is, many of us have no idea we’re using them.

Nurseries and garden supply stores know their customers tend to overlook plants showing insect-inflicted damage and gravitate instead toward the picture-perfect flowers. Some states mandate pesticide applications to prevent the spread of certain pests. Either way, toxic levels of insecticides and high levels of fungicides have been found in nursery plants - even in plants advertised as native pollinator plants. Before purchasing, always ask if the seeds or plants have been exposed to pesticides. If the salesperson doesn’t know, go someplace else. It’s better to be safe than sorry.

It Doesn’t Stop ThereThe use of neonics extends far beyond residential use. Many farmers are unaware that the commercially available corn, soybean, wheat, and cotton seeds they purchase are treated with neonics. At least 160 million acres of cropland across the US are sown each year, with no precautions taken for the safe handling, storage, or disposal of these seeds. There is no federal oversight once the seeds have been coated. The EPA does not consider neonic treated seeds to be a pesticide application.

The toxic chemicals are also available in liquids and granules and distributed under various names: imidacloprid, clothianidin, acetamiprid, thiamethoxam, and thiacloprid. Neonicotinoids are water-soluble and can be easily absorbed by a developing plant—however, only approximately 5% of the active ingredient is absorbed by the target crop. The rest disperses into the wider environment contaminating the soil and water, harming terrestrial life as well as freshwater species. As a result, some states have taken action and enacted legislation limiting or restricting the use of neonics. Still, there is a long way to go before pesticides are properly regulated or taken off the market.

Human error in pesticide applications has been known to lead to human injury and death to wildlife, bugs, and all other kinds of critters. For instance, bee kills in domesticated honey bee hives have been well documented. Unfortunately, large-scale impacts on wild bees are poorly studied since they generally occur away from human observation.

Yet sometimes, the evidence cannot be denied. In June 2013, dinotefuran, a type of neonicotinoid was applied to linden trees in a shopping mall parking lot in Wilsonville, Oregon. That incident caused the largest documented pesticide kill of bumblebees in North America. Between 45,830 and 107,470 bumblebees originating from between 289 and 596 colonies were killed.

In Mead, Nebraska, an ethanol plant, AltEn, used seed coated with fungicides and insecticides to produce the fuel additive. Residents reported a terrible stench, eye and throat irritation and nosebleeds, dogs becoming ill, and disoriented or dying bees, birds, and butterflies.

Officials found piles of the smelly, lime-green mash of fermented grains accumulating on the grounds of its plant. Some of the mash had been used as a ‘soil conditioner’ by local farmers. In addition to the massive amounts spread across the acreage, still more had leached and spilled out of wastewater lagoons into adjacent waterways.

Researchers say the waste was dangerously polluting water and soil and probably also posing a health threat to animals and people with levels many times higher than what is considered safe. High levels of 10 pesticides were found in the plant lagoon, and at least four pesticides in the corn used by AltEn are known to be detrimental to humans, birds, mammals, bees, freshwater fish, and other living creatures.

Now the questions are: How is that mess going to be cleaned up? Where will the waste go? How long will it take, not only to clean up the green slime but to rid the environment of all the residue pesticides? What are the residents and wildlife supposed to do in the meantime?

You Can Make a DifferenceNeonicotinoid pesticides were first introduced in the 1990s and since then have become the most widely used class of insecticide in the world. Unfortunately, many folks have never heard of neonics and are unaware of the systemic insecticides that permeate the roots, leaves, foliage, pollen, and nectar of plants affecting all creatures that come in contact with the poison.

Neonic treated seeds are primarily sold to farmers, but seeds coated in fungicides are available for gardeners. You can usually tell if a seed has been treated by its shiny sheen or a bright color.

One thing you can’t tell by appearance, though, is if your plant has been treated with a systemic pesticide. You have to ask. Sadly, even pollinator-specific plants such as milkweed have been found to contain neonics. There have been a number of occasions when carefully cultivated patches of milkweed became a graveyard instead of a waystation for the Monarch butterfly’s caterpillars.

Xerces’ guide, Buying Bee-Safe Plants, includes tips and questions to use at the nursery and suggests four ways to help you find plants that are safe for bees and other pollinators:

- Ask for USDA certified organic plants and seeds

- Avoid plants grown with neonicotinoids and similar insecticides

- Shop at nurseries that practice pollinator-friendly pest management and/or

- Grow your own plants

You can help spread the word by informing your friends and neighbors and encouraging them not to purchase any plants treated with pesticides. From a business perspective, the power of the dollar often speaks louder than any activist’s bullhorn. If customers won’t buy the pesticide laden plants, the shop owner will have to change her inventory. From there, the word will continue to reach new listeners, including the ears of legislators who can make a lasting difference.

Trying to solve garden pest problems with toxic chemicals only causes a domino effect of negative results. Break the chain and help us start restoring Mother Nature’s balance.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed